Blog Layout

Battle of Sherburn-in-Elmet, Yorkshire - 15th October 1645

M Turnbull • Oct 15, 2020

The Overshadowed, Yet Pivotal, Yorkshire Battle.

If you ask anyone about the most decisive battle of the English Civil War, they are most likely to answer Naseby, which took place in Northamptonshire on 14th June 1645. Considering this is where King Charles I’s veteran infantry were obliterated and his cabinet of private letters captured, then you can understand why. The royalist cause is billed as being irretrievably finished after Naseby and victory for Parliament merely a matter of time.

But … thousands of the King’s elite cavalry survived. His Lieutenant-General in Scotland, the Marquis of Montrose, had just secured that entire kingdom. New infantry recruits were due from Wales and more reinforcements expected from Ireland. Naseby was a decisive defeat for the King, but it was an almost forgotten battle at

Sherburn-in-Elmet

four months later that dealt the real killer blow.

Lord George Digby

– an English Rasputin – had been King Charles’s Secretary of State since 1643. He was a silver-tongued, self-obsessed man with a devious streak and a hypnotic charm. Like an impervious cockroach, he would successfully crawl out from under the destruction he had wrought in the royalist ranks. The hard shell of this deluded politician had the King believe that every setback was someone else’s fault; and that there was always a silver lining just around the corner. It was Lord George Digby who was placed in command of the King’s elite cavalry. His last hope.

On 13th October 1645, at Welbeck, Digby’s fateful appointment as Lieutenant-General of the forces north of the River Trent was confirmed. It seems to have been the result of his private connivance, because none of the King’s officers – including the council of war – had any inkling that it was going to happen until the monarch revealed the decision in a speech to his cavalrymen. And well may Digby have wanted it this way, for the King had no less than 24 officers with him ranked colonel or above who could have filled the role, and the surprise prevented any coherent protest. Of course, Digby claimed never to have known that the appointment was coming and wrote, ‘At half an hours warning having (I protest to God) not dreamt of the matter before, I marched off from the rendezvous’.1

The experienced Sir Marmaduke Langdale was to support him. Typical of the two-faced Digby was the fact that he had described Langdale as ‘a creature of Prince Rupert’s’2

but now that he needed this ‘creature’ he embraced Langdale.

The Parliamentarian, John Rushworth, noted Digby’s next move. ‘It was agreed, that the northern horse, commanded by Sir Marmaduke Langdale, my Lord Digby … should march into the north, to join [the King’s Scottish general, the Marquis of] Montrose’.3

Once united, Digby and Montrose would restore royalist fortunes in England. The one snag, unbeknown to Digby, was that Montrose had been defeated several weeks earlier.

Nevertheless, Digby’s small force struck at Doncaster, beating up some of the enemy there and then scattered some more at Cusworth. Upon nearing Sherburn-in-Elmet, Digby ran into an infantry regiment of 1000 parliamentarians commanded by a Colonel Wren. The royalists went on to defeat Wren’s force, but no sooner had Digby taken them prisoner and had them hand over their arms and weapons, than he was informed of the approach of a second enemy detachment.

The parliamentarian Colonel Copley led 1200 cavalrymen to the rescue of their colleagues. The Battle of Sherburn-in-Elmet that followed is a confused affair. It appears from most accounts that Digby’s small army had become split. Copley’s men encountered only half of the royalists, commanded by Sir Marmaduke Langdale, who buoyed his men up with a speech:

‘Gentlemen you are gallant men, but there are some that seek to scandalize your gallantry for the loss of Naseby field. I hope you will redeem your reputation, and still maintain that gallant report which you ever had. I am sure you have done such business as never has been done in any war with such a number’.4

It was a fierce contest, but Langdale’s men began to get the upper hand. So far, so good for the royalists. But yet another detachment of parliamentarians was closing up under Colonel John Lilburne, a north-east man and well-known Leveller. Langdale could not contend with both Copley and Lilburne together. Now was Digby’s moment for glory; the chance for him to reinforce his subordinate and secure a victory; one which would establish him as a crusader for the King’s flagging cause and silence his many doubters.

When some of Copley’s hard-pressed men broke and fled through Sherburn’s streets, Digby took them to be Langdale’s troopers. Thinking that his royalist sidekick had been routed, Digby marshalled his troops and simply left! Abandoned by their commander, Langdale’s 1000 cavalrymen could not withstand Lilburne’s added might and eventually broke with the loss of up to 700 men, the bulk of which were taken prisoner. The victorious parliamentarians went on to free Wren’s men and took back the stash of arms and weapons that Digby had piled up in Sherburn’s streets. Though Digby and Langdale escaped their clutches, the parliamentarians did, however, secure a greater prize; Digby’s coach, containing all of his private correspondence. It was bundled up and sent down to London for Parliament’s urgent attention. The breadth of secrets they revealed was worth a hundred victories. Parliament even established a committee to scrutinise the letters, and after wringing out every last detail, they handed them over the to their Scottish allies, using the findings as a means of keeping them on side. Ironically, the site where the coach was taken at Milford, about one mile from the parish, is reputed to be where the dead were buried.5

The sixty-nine letters revealed everything from the King’s hopeless position, cut off at Newark, identified a spy in the heart of Parliament (who was summarily arrested), documented the movement of the Prince of Wales, who was to be sent into the West Country, as well as the names of many senior royalists who were pushing the King to make peace. The writing was well and truly on the wall. One deeply personal letter betrayed King Charles’s innermost thoughts when he wrote that he had no doubt but of his ruin.

Worse still was the revelation of the destined route of some much-needed munitions, sent from the Queen in France, along with news that the King of Denmark was prepared to send support.

Dame CV Wedgewood, in her book ‘The King’s War’ reveals what happened to Digby and Langdale’s surviving troops. ‘On a false rumour that Montrose [the King’s Scottish general] had rallied and was in Glasgow, they pressed on to Scotland as far as Dumfries, where they learnt the truth and turned back again, planning to winter in the inaccessible region around Cartmel, between the mountains and the sea and await (as always) the coming of the Irish. Their troops, lacking all confidence in them now deserted by the hundred’.6

The last of Digby and Langdale’s forces were defeated at Carlisle Sands and the two men took ship to the Isle of Man.

REFERENCES

1. Thomas Carte, A History of the Life of the Duke of Ormonde, VI, p. 303. (1736)

2. State Papers, Collected by Sir Edward Hyde. Vol II, p. 199. (1773)

3. John Rushworth Memoirs, Part IV. Vol. 1, p. 123.

4. Christopher Hibbert, Cavaliers and Roundheads, p. 258. (1993)

5. Edmund Bogg, The Old Kingdom of Elmet: York and the Ainsty District. (1902)

6. C.V Wedgewood, The King’s War, p. 504. (1958)

If you've enjoyed reading about the War of the Three Kingdoms, you can read more about it in my historical novel,

Allegiance of Blood. I am also working on a series of novellas for Sharpe Books, which will be set in the civil war. More about those in early 2021.

By M Turnbull

•

13 Sep, 2020

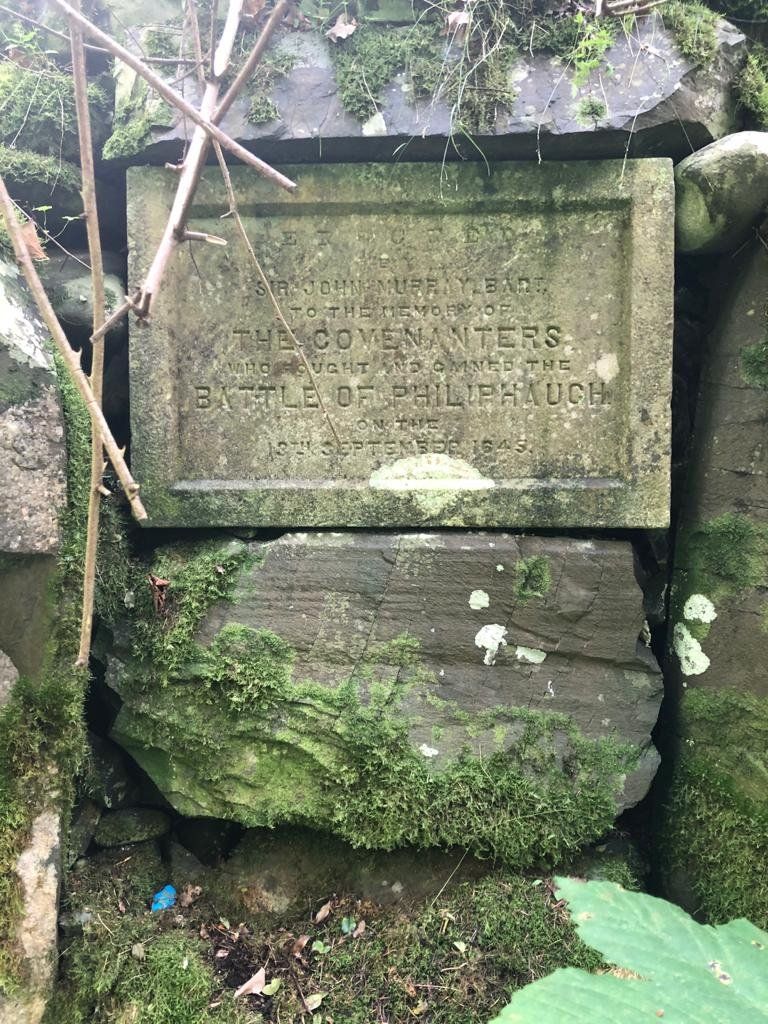

⚔️The Battle of Philiphaugh⚔️ 📅13th September 1645 - 375th Anniversary 🗺 Near Selkirk (c.30 miles from today’s Scottish-English Border) For nearly four weeks, James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, had secured the whole of Scotland for King Charles I. It had taken just over a year of stunning victories to break the Covenanter government, who had allied with the English Parliament during the War of the Three Kingdoms. Montrose had set the date for a Scottish Parliament, and was preparing to lead his army into England to work a second miracle, but Philiphaugh ended the dream. Though it was personal jealousies, ambitions and greed, that led to Philiphaugh. The problems had started in Glasgow. The pinnacle of success had turned into a slippery slope, and for the first time without an enemy army on their tails, most royalist soldiers just wanted to enjoy their success. They spared little thought about the the Covenanter army that was still deployed in England – part of which, under Major-General David Leslie, was hurrying back to Scotland. To add to their frustrations, Montrose had just punished some within his ranks who had fallen to plundering Glasgow. Desertion was on the increase. At this moment, Viscount Aboyne, who represented the powerful Clan Gordon, left Montrose and ‘seduced all the rest of the northern forces to depart’. (1) Aboyne was smarting because he had been passed over for the position of General of the Horse, therefore took his cavalry and checked out. King Charles had sent his remaining elite cavalry north with orders to link up with Montrose. At the same time, the slippery lords of the south – the Border Earls of Home, Roxborough and Traquair – now verbalised pledges of support. But they wailed to Montrose of their struggle to muster their clans and called for his personal presence to help them; his presence in the Scottish Borders, which was a Covenanter hotbed, and which was where Leslie was fast approaching. Montrose’s internal problems did not stop here. With his men pushing for leave to see their families, attend the crops and take their booty home, he had no alternative but to agree to a 40-day furlough, and Alexander MacDonald left with 3000 of them to ensure that this was adhered to. Far better agree to a limited absence, than have them desert. George Wishart, a contemporary wrote, ‘Yet [MacDonald] had resolved not to return, and he never again set eyes on Montrose. Not content with the force of Highlanders, more than 3000 of his bravest men, he secretly seduced 120 of the best of the Irish, whom he carried off with him also as a bodyguard.’(2) The Irish contingent was further decreased when their leader – Montrose’s right-hand man, Alisdair MacDonald (‘MacColla’) – took more men away for a raid upon Galloway. With his numbers wasted, Montrose was left to feed upon the shaky promises of the Border Earls and marched his army south. When he reached the Borderlands, the Earl of Traquair’s son arrived with a few cavalry in support, but the Earls of Home and Roxborough were conspicuous by their silence. He now had 500 Irish infantry and 1120 cavalrymen, whereas David Leslie had reached Berwick with near to 6000. Leslie’s plan was to seize Edinburgh and put a halt to the coming Parliament, but he changed his mind very quickly. Wishart gave his opinions of where this u-turn stemmed from. “Letters had reached [Leslie] containing accurate information of Montrose’s strength, which consisted only of 500 Irish foot and a few raw undisciplined horse … It has commonly been reported that Traquair was the source of this information. This I cannot assert for truth; but it cannot be denied that he ordered his son Linton that very night to withdraw from the Royalists as fast as he could.”(3) Montrose also changed his plans. The force King Charles had sent north had been defeated and the marquis resolved to head west to more friendly territory when he could recruit. On 11th September 1645, Leslie left his infantry behind and raced after Montrose with 4000 cavalry. The next day they attacked royalist outposts, hearing that Montrose was at Selkirk with his cavalry, while the infantry were bivouacked at Philiphaugh. Reports of Leslie’s approach were not taken seriously by the royalists until Captain Blackadder, a scout, ‘returned with his men in a great fright, and reported to Montrose at breakfast ‘that a great armie was advancing within a mile of the toune.’ (4) John Rushworth, a parliamentarian, said that Montrose resolved ‘to make use of all Advantages of Ground, having on the one Hand a deep Ditch, on the other, Dykes and Hedges, which he caused to be lined with Musqueteers; and tis like had been better prepar'd, if he had not been deceiv'd by the Mistake of his Scouts, who assured him no Enemy was near’.(5) Leslie wasted no time. He attacked the royalist infantry, but being impeded by a burn, the marksmanship of the Irish and charged by a few of the royalist cavalry, he was repulsed. Despite this, all was not well in Montrose’s camp. Many of the royalist officers were absent and never reached the field, while only 10% of their 1120 cavalry mounted any opposition. The rest were ‘more intent upon baiting their horses than maintaining their lives with honour’. (6) The Earl of Airlie led the 120 royalist horsemen that kept the Covenanters off their left flank. With no such horsemen on the royalist right flank, Leslie soon resolved to strike there and also sent 2000 of his force clattering over the bridge towards Selkirk, and then around the royalists, thus cutting off any line of retreat and threatening their rear – this was his masterstroke. Montrose, forming up 30 horsemen, was ready to fight to the end, but his officers and friends persuaded him that his death would also kill off the royalist cause. They reminded him of MacColla’s Irishmen in Galloway, of the furloughed 3000 and reluctantly, Montrose left the field, defeated for the first time. Leslie offered quarter to the royalists, but was not strong enough to keep his word, especially when besieged by the frenzied church ministers who called for retribution against those who had brought their regime to its knees. Wishart summed up the end. ‘For the [royalist] foot there was little hope in flight; they stood firm and fought resolutely, till offered quarter, when they threw down their arms and yielded. But, notwithstanding the promise of quarter, those defenceless men were every one butchered in cold blood by Leslie’s own orders, an indelible blot of savage cruelty and treachery on the glory and renown which he had gained abroad.’ (7) Dame CV Wedgewood stated in her book, ‘The ministers who attended [Leslie’s] army protested, and Leslie, weakly conceding that he had given quarter only to the commanders, allowed his men to slaughter first the camp followers, the women and boys, and later, on the march, little by little to hang and drown the men.’ (8) In Nov 1645, The Scottish Estates ordered the execution of any prisoners from the battle and in 1810, large quantities of bones and skulls were found near Newark Castle, in a field known as Slain Mens Lea. These are thought to be some of the royalists who were murdered.(9) Two items to escape Leslie’s grasp, however, were the royal standards. The infantry pennant was saved by an Irishman who stripped it from its flagpole, wrapped it around his body and fought his way through the enemy, sword in hand, to deliver it to Montrose that night. The grateful marquis made the man the bearer of the standard and adopted him into his lifeguard. The other was rescued by William Hay, the brother of the Earl of Kinnoul, who fled with it to England. After the dust had settled, he set out on an intrepid journey north to reunite it with Montrose. On the very day of the battle, one of Leslie’s men arrived in Berwick to report his victory. It occasioned Philip Wharton to write to the English Parliament: "Sir James Hackett this Day came from the Scottish Army, and made a Report unto us of a Fight that happened betwixt Lieutenant General Lesleye's Forces and Montrosse, at a Place near Silcreeke, about Twentysix Miles from this Town, where God of His great Mercy appeared mightily for us. They killed and took Prisoners Twelve Hundred of their Foot, put all the Irish to the Sword … Montrosse is fled towards the Hills with his Horse, and ours in Pursuit of them’.(10) For David Leslie, who had finally saved the Covenanter skins by defeating their nemesis, he was voted a gold chain and a handsome reward. The victory was trumpeted in every corner of the kingdom in a bid to break Montrose’s spell, but the Covenanters knew that as long as the marquis was at large, they were not safe. Their desperation had long been signalled by the price of £20,000 that had been offered for Montrose – dead or alive – and which was enough to keep an army of 5000 men in the field for three weeks. One battle would not lose the war. The end came not through further battles, but eight months later, when King Charles surrendered his person to the Scottish army at Newark, in England. REFERENCES 1. The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose 1639-1650 by George Wishart 2. The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose 1639-1650 by George Wishart 3. The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose 1639-1650 by George Wishart 4. The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose 1639-1650 by George Wishart 5. John Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: Matters relating to Scotland, 1645', in Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 6, 1645-47 (London, 1722), pp. 228-238 6. The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose 1639-1650 by George Wishart 7. The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose 1639-1650 by George Wishart 8. The King’s War 1641-1647, by C.V Wedgewood 9. Information Board, Philiphaugh, at site. 10. House of Lords Journal Volume 7: 19 September 1645 Pages 583-588 📷 The blog logo features the plaque from the Philiphaugh monument dedicated to the 15 Covenanter dead. (No memorial exists for the hundreds of royalists)

By M Turnbull

•

11 Aug, 2020

The Battle of Kilsyth can be called the battle for Scotland. James Graham, Marquis of Montrose and his counterpart, Alisdair MacDonald (known as MacColla) led the royalist army into the lowlands. With them came a reputation; one of victory, for they had secured five in a row over the Covenanters and all within the space of 11 months. The Covenanter government of Scotland, led by the powerful and ruthless Marquis of Argyll , had allied firmly with England’s Parliament and had their army engaged in the deep within that kingdom. Montrose and MacColla had gradually worn away all the armies that the Covenanters could raise to try and oppose them getting a foothold in Scotland. Argyll had even desperately recalled regiment after regiment from England, but to no avail. On 15th August 1645, only one army was left under Covenanter control in Scotland and it now looked set to meet Montrose. Parliament had fled Edinburgh for the safety of Stirling, though it wasn’t just fear of Montrose that had the assembly on the run, but also the plague, which had them shift again, this time to Perth. The Covenanter General Baillie had proffered his resignation after the covenanters fifth defeat, but it had been declined. He was placed in charge of the last army, though in title only, for along with that army marched a committee. Yes, a group of backseat drivers, led by Argyll (the boss himself) was on hand to advise – and overrule – General Baillie. It seemed comprised of all of the commanders that Montrose had defeated. As if their defeat had relegated them to a seat upon a body of men who would attempt to make sure the next general was more fortunate. Baillie had to face doing battle with this cursed committee as well as Montrose. "They wanted Montrose's head immediately" When it came to the Battle of Kilsyth, Baillie didn’t want to fight it at all. He wished to harry Montrose, keep him in the lowlands and out of his powerbase, and wait for further reinforcements. Not that Baillie needed them, outnumbering Montrose three to two, but if he could delay and receive another thousand or so, then what could be the harm? The committee disagreed. They wanted Montrose’s head immediately and had their own personal revenge driving their decisions, therefore Baillie was forced to accede to them. At Kilsyth, 12 miles from Glasgow, Montrose drew up his men in a valley beneath the hill upon which the Covenanters had planted themselves. Stone walls offered Montrose’s position some defence. The day was hot and humid, much like the weather these past few days in 2020. Recognising the difficulty this would pose in the heat of battle, Montrose ordered his troops to strip to their white shirts and this brazen disregard for protection seemed to send the committee into spirals of rage. Argyll overruled Baillie again and refused to allow the Covenanters to lead a full-frontal attack. Instead, he wanted to catch Montrose in a trap from which he could not escape and ordered the Covenanter army to adjust its position. As such, in the face of the royalists, the Covenanters marched towards another hill, which if gained, would allow them to attack Montrose in the rear. However, Montrose was too quick for them. The wily fox had some foot soldiers occupy the target hill, thus thwarting Argyll. The Covenantor troops, attempting to remain hidden behind the lay of the land, were discovered when some of their force attacked – against orders – the advanced posts of Montrose’s army. The problem for them was that the men they picked upon were MacColla’s fierce Irishmen; men who had a vendetta, for the Covenanters had attacked and killed some of their womenfolk camp followers of late. Thus engaged, MacColla’s men surged uphill and right at the main Covenanter force. Montrose, seeing that battle was to be joined, turned to old Lord Airlie, who commanded his cavalry. ‘They yonder have engaged themselves too far by the foolishness of their youth. It is for the discretion of age to set it right’. With Montrose’s words in his ear, Airlie charged to the support of MacColla, followed by Montrose and the infantry. Airlie broke one wing of the enemy’s cavalry and drove them upon their colleagues. With Airlie’s second charge, the Covenanter army began to waver. And then Argyll, the Committee Chairman, fled the scene; an action he had become quite wont to do. In Argyll’s tracks followed the Covenanter cavalry, and left to their own devices, their infantry had no alternative but to break and flee. "The one-year miracle of Montrose - six stunning victories in a row" The Battle for Scotland had cost Montrose 6 men, but it left nothing that could be called an army in Scotland to oppose him. Argyll’s flight took him out of the country altogether, and he only halted in Berwick. Edinburgh and Glasgow recognised Montrose’s ultimate victory and opened their doors to him, fully expecting to be thoroughly plundered, yet Montrose kept his men camped outside of both towns, only entering Edinburgh with a handful of retainers. This way he avoided looting and also proved his determination to unite the nation under the royal banner. He offered a pardon, in the King’s name, to all those who would lay down their arms. Word arrived that King Charles had suffered a catastrophic defeat in England, at the Battle of Naseby, making Montrose’s Scottish success all the more imperative. But also in the post came orders from the King, with permission for Montrose to call a Scottish Parliament in his name. A date was fixed for mid-October. And then Montrose, recognising his brave counterpart, knighted MacColla on behalf of the monarch. The one-year miracle of Montrose – six stunning victories in a row – united Scotland under King Charles’s standard for a brief moment in time. The Covenanter cavalry under the command of General David Leslie were hammering home to prevent Parliament from assembling, but also to expel Montrose from Scotland once and for all. If you want to read more blog posts, you can navigate the website via the links below. Hope you have enjoyed reading!

By M Turnbull

•

10 Jul, 2020

The Battle of Naseby was the first time that the King’s veteran ‘Oxford army’ met the newly formed New Model Army, which was commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax. Fairfax’s men had their first blood at Naseby, vanquishing the royal infantry and almost four weeks later, they were hard on the heels of the other major army that the King had tucked away in Somerset. Lord George Goring, a hard drinker who stumbled between greatness and ghastliness, was in command of the royalists. He had itched for an independent command in the South West and once he had secured it, he was unwilling to leave his little kingdom - even for the King himself. For, while King Charles was preparing for Naseby, Goring was meant to have brought his army up in support, but had dallied for so long that by the time he was ready, the monarch had long since been defeated. Goring also had history with the South West. His soldiers had preyed on the people of the region for months, plundering and being nothing but brutes – so much so that the people had risen up and petitioned the Prince of Wales for help. But by July 1645, the royalist cause was on the wane. When Sir Thomas Fairfax led the New Model Army down the South West peninsula, hemming goring in, there was to be no escape. The King, meanwhile was taking refuge near the border of South Wales, where the coming conflict between Goring and Fairfax seemed far from his mind. Awaiting Welsh recruits, he penned a letter full of optimism one week after Naseby: ‘and assure you that as myself is in no ways disheartened by out late misfortune, [Naseby] so neither is this country, for I could not have expected more from them than they have now freely undertaken … so that (by the grace of God) I hope to recover my late loss with advantage if such succours come to me from that kingdom [Ireland] which I have reason to expect…’ The King’s confidence was just as high as Goring’s, who fell back upon Fairfax’s advance. Like Jekyll and Hyde, Goring the Great now took precedence. He sent his drinking buddy, George Porter, with some of his troops back to Taunton. This move perplexed Fairfax, who wondered what Goring was up to, and made him split the New Model Army; 4000 of his 14000 being sent after Porter. Goring’s plan had worked. He now drew up his 7000 men and prepared to do battle with Fairfax, whose reduced force of 10000 offered better odds. In the hilly countryside around Langport, which was wet and soggy from the summer downpours, the royalists zeroed in on the small crossing over a brook. The lane that crossed the water was bounded by tall hedgerows which Goring lined with musketeers. At the exit to the lane, he deployed his cavalry and two cannons on the rising slopes. With much more horsemen than Fairfax, he was extremely confident. When Fairfax arrived, he quickly realised that his only way of doing battle was across the hedged lane. The brook itself put paid to any other option. The crossing was a death trap and Fairfax knew it, but he also knew his men. First, he drew his artillery into position and used their superior numbers to silence Goring’s two pieces. By noon, the time was ripe to release his infantry and Fairfax ordered 1500 musketeers into the lane, commanded by Colonel Rainsborough. Despite the hail of lead shot, Rainsborough’s men took out enough of the royalist musketeers to allow Fairfax’s cavalry to advance. Four abreast they galloped through the lane and attacked Goring’s army – repelled at first, but then as more of the New Model Army emerged into the field and attacked Goring’s flank, it was clear that the royalists were finished. At this point Goring the Ghastly came to the fore and he ordered the houses of Langport to be set alight to prevent the New Model Army pursuing him. Despite the flames, Cromwell, with fire in his belly, led his men in pursuit and exclaimed ‘to see this, is it not to see the face of God?’ The New Model Army took 2000 royalist infantrymen as prisoners and 1000 of their cavalry; it would now be a matter of time before Goring’s end was nigh. Three weeks after Langport, the King can be found picking up his quill once more, but this time with a melancholy that echoes in his words: ‘It hath pleased God, by many successive misfortunes, to reduce my affairs, of late, from a very prosperous condition to so low an ebb as to be a perfect trial of all men’s integrity to me’. If you would like to read more of my articles, please use the links below. More details about my civil war novel, Allegiance of Blood, can be found by returning to the home page.

By M Turnbull

•

30 Jun, 2020

Royalist army: Commanded by the Marquis of Newcastle. Parliamentarian army: Commanded by Lord Ferdinando Fairfax and his son, Sir Thomas. Adwalton Moor. An inevitable battle that saw royalists and parliamentarians vie with each other over the hand of Bradford, a town of much consequence. The royalist Earl of Newcastle may have held most of Yorkshire for King Charles, but two notable absences were Hull and Bradford. What’s more, Bradford was a town within the heartlands of his opponents, Lord Ferdinando Fairfax, and his son Sir Thomas; a town he must have if he was to deprive the duo of a base, as well as supplies, and recruits. Lord Fairfax, however, was very much awake to the danger, and decided not to simply wait for the royalists to arrive at the gates. Instead, he was up at 4am on 30th June 1643, intending to march out and confront his enemy. Both sides headed directly towards each other that morning and it was at the highest point of a moorland ridge that they met – near the village of Adwalton. The Earl of Newcastle occupied the ridge with ten thousand men, having dragged the carcasses of two immense cannons behind him all the way. Named ‘Gog’ and ‘Magog’ these deadly demi-cannons now eyed the four thousand parliamentarians who deployed only 500 yards away. The parliamentarians were heavily outnumbered. Lord Fairfax’s army was an amalgamation of men drawn from their remaining Yorkshire garrisons; Bradford, Halifax, Pomfret, (Pontefract) Saddleworth and Almonbury. It was boosted by troops from Lancashire. What was worse, was that part was made up of civilians – ‘clubmen’ – who were meanly armed. Lord Fairfax, commanding the infantry in his centre, held the clubmen in reserve. One parliamentarian intimated that the clubmen were only “fit to do execution upon a flying enemy” and not much more. General Gifford commanded the parliamentarian cavalry on the left wing, while Sir Thomas Fairfax commanded those on the right. There was one big difference between the two cavalry wings; Sir Thomas’s position was in a dip, out of sight of the rest of his father’s force. By contrast, the royalists had only half the number of musketeers, but were superior in cavalry. Their right wing of horsemen, led by General King, was immediately hampered by coal pits, therefore found it difficult to deploy. Over on the left wing, Sir Thomas Howard’s horsemen faced Sir Thomas Fairfax. Sir Thomas Fairfax made the most of his position. Based in an enclosure with one entrance gate that was the width of five or six horses, he distributed one thousand musketeers around the hedges to make good his numerical disadvantage. When ten or twelve troops of royalists attacked, funnelling straight down to the gateway, Fairfax recorded how they fell into his trap: “they strove to enter, and we to defend; But after some Dispute, those yt entered ye passe found sharpe entertainmt; & those yt were not yet entred, as hot welcome from ye Musketeers …” The royalists who got through the gate were set upon by Fairfax’s cavalry and repulsed, while those bottlenecked behind their colleagues were picked off by his musketeers. One of those bullets had Sir Thomas Howard’s name on it, and when the royalist colonel was felled, his men retreated. But thirteen to fourteen troops of fresh royalists were soon galloping up to the gateway again, ready to avenge Howard’s death. This time more succeeded in breaking through, but, faced with the same difficulties, and after their leader, Colonel George Heron was also killed, they likewise fled. This time Fairfax’s men chased after them. Fairfax impetuously led this pursuit for six hundred yards until encountering royalist pikemen. He then turned and headed back to his enclosure. Gog and Magog, meanwhile, roared out their indignation over the deaths of the two royalist colonels and one shot killed four parliamentarians who were stripping the dead Colonel Heron of his possessions; an act of divine justice, Sir Thomas Fairfax judged. Following on from Fairfax’s success, General Gifford led the other wing of parliamentarian cavalry against the royalist infantry, at which point it all became too much for Lord Newcastle, who prepared for retreat. But the resolute determination of one man prevented this. Colonel Posthumous Kirton (whom Fairfax described as a ‘wild and desperate man’) urged Newcastle to let him charge the enemy with the earl’s own infantry regiment, the infamous ‘Whitecoats’. Having refused to have their coats dyed, they had sworn to colour them with the blood of their enemies, and this moment offered just such an opportunity. The Countess of Newcastle, in her later biography of her husband, described the courageous actions of the Whitecoats: ‘At last the pikes of my Lord’s army, having no employment all the day were drawn against the enemy’s left wing, and particularly those of my Lord’s own regiment … who fell upon the enemy, [who] forsook their hedges, and fell to their heels’. Sir Thomas Fairfax, out of sight in the dip of his enclosure, was oblivious to this turn of events. But he later declared that Gifford ‘did not act his part as he ought to have done’. The royalist cavalry took heart made another charge, while Gog and Magog spat their fury against the parliamentarian infantry blocks. Hopelessly outnumbered, Lord Fairfax sounded the retreat, but did not inform his son, Sir Thomas, who continued fighting until he was practically surrounded. When Sir Thomas finally found out about his father’s absence he quickly withdrew while he still could, not drawing rein until he arrived in Halifax, eight miles away. The royalist, Sir Philip Warwick, stated in his memoirs that victory at Adwalton Moor ‘made the earl [of Newcastle] seem lord of the north, for from Berwick to Newcastle, and from Newcastle to Newark, all was the king’s …’ The one thing that Sir Philip didn’t mention was Hull; a thorn that stuck in Lord Newcastle’s side and prevented him from marching south to join forces with the King. Had Hull fallen, the parliamentarian cause would most certainly have toppled soon afterwards.

By M Turnbull

•

29 Jun, 2020

⚔️ The Battle of Cropredy Bridge ⚔️ 29 June 1644 Cropredy Bridge was the first in a two-part encounter which stunningly transformed King Charles's position in the south. Three days later, in the North, the royalist forces under Prince Rupert would suffer a devastating blow at Marston Moor. June 1644 did not start well for King Charles at all. Holed up at his headquarters in Oxford, the King’s army was depleted and two enemy armies were on the loose. He was at an immediate disadvantage in numbers even if he only had to contend with one of those forces, never mind both. As a result, a rash decision was taken that the royalists would abandon Reading, despite it only recently being agreed that the garrison would be maintained. As soon as 2500 men marched out of the town to boost the King’s numbers, Parliament sent its armies to occupy it, allowing them to push ever closer to the star prize; Oxford. One of the armies of Parliament, commanded by the Earl of Essex, headed towards the north of Oxford while the other, led by Sir William Waller, marched south of the city. Both looked set to encircle Oxford and starve the King into submission, and if successful, this would deliver the monarch into their hands and end the war. But King Charles had a plan, and that firstly involved breaking free. On 3 June, he clattered out of Oxford with a force mostly consisting of cavalry and headed west towards Worcester, drawing the attention of the two armies who pursued in a cat and mouse chase. The two tomcats, however, did not get on and decided to part ways - Essex would march into the south west and leave Waller to catch the King. Waller eyed his royal prey and watched as it now scurried north, shadowing as close as he could. But the wily King had his infantry transported onto boats and sailed them south again down the River Avon, allowing his army to outmanoeuvre Waller and reach Oxford once more, where he collected the rest of his troops. These reinforcements put the King’s force equal in number to Waller’s - each man commanded five thousand horse and four thousand foot. But the King was far from out of the woods. There was still the risk that Waller and Essex might reunite, so it was important that he continued to lure Waller away from his partner. Therefore King Charles was eastward bound, threatening Parliament’s territories in East Anglia; a successful move which prompted Parliament to instruct Waller to stop him. By 27 June the King and Waller were five miles away from each other. On 29 June, the King’s army was near Banbury, marching on the east side of the River Cherwell, while Waller’s men shadowed them on the West Bank like ghostly silhouettes. Within one mile of each other, neither side wished to attack first and it was news that 300 cavalry were on their way to join Waller that eventually spurred King Charles on. He hastened his march in a bid to cut off this enemy detachment and defeat it before it reached Waller. In doing so, the King’s army became strung out and Waller found it too tempting an opportunity to pass up. The parliamentarian crossed the Cherwell at two points, aiming to nip the King’s rearguard within a deadly pincer movement. Initially Waller managed to cross Cropredy Bridge, but he was soon driven back on both accounts and the King’s men took possession of eleven artillery pieces in the process. By evening both armies still faced each other, though neither could secure outright victory. The King, having lost few men, offered Waller a pardon, but the commander refused to treat with the monarch. After hearing that further reinforcements were on their way to Waller, the King took the chance of slipping away along with the daylight. Under cover of night and with his prize guns, the King left Waller licking his wounds over the loss of 700 soldiers. The dawn of a new day shone kindly upon the King’s cause, for Waller’s demoralised army was soon wracked by desertion and mutiny and left lame. It was now of no threat to the King, who turned and followed Essex ever deeper into the south-west, aiming to finish off the second army that had once threatened him. This was King Charles’s greatest personal military success of the entire English Civil War, and he would go head to head with Essex in 6 weeks time in an effort to add to his laurels. While researching this narrative, I came across come of Waller's own words, which revealed that he experienced one of his many, many near-death experiences at Cropredy: a most unusual one: "At Cropredy in Oxfordshire, I escaped a great danger of the like nature, when being with my officisers att a councell of warr, the floore of the roome (where I was) sunke under me, and I lay over-whelmed with a great deal of lumber that fell upon me, and yet, blessed be God, I had no hurt att all." If you've enjoyed reading about the War of the Three Kingdom's, be sure to look at the other articles on my blog by clicking on the link below. You can also find out more about my civil war novel, Allegiance of Blood , which features the King and Waller as characters.

By M Turnbull

•

04 Jun, 2020

⚔️⚔️BATTLE OF NASEBY 1645⚔️⚔️ 375th Anniversary 14th June 2020. 🔹 10 biographies over 10 days to mark this date 🔹Each 375 words 🔹Covers the commanders of each side 📅 DAY 1 📅 SIR MARMADUKE LANGDALE 1598-1661 Born in Beverley, Yorkshire Marmaduke was renowned in his lifetime for two reasons; leadership of the elite royalist cavalry unit called the ‘Northern Horse’ and also his Roman Catholicism. (Marmaduke’s grandfather, Anthony Langdale, had been forced to flee to Rome after the Reformation.) Religion aside, the young Marmaduke joined the 1620 expeditionary force that was sent to the Palatinate to fight the Catholic armies of Spain. In 1626 he married Lenox Rodes in St. Michael le Belfry, York. By 1639 he’d been appointed High Sheriff of Yorkshire, but in the same year lost his wife during childbirth and then his father-in-law died. He began opposing royal taxation and the King’s leading minister, the Earl of Strafford, wrote of Marmaduke: 'that gentlemen I fear carries an itch about with him, that will never let him take rest, till at one time or other he happen to be thoroughly clawed indeed’. At the outbreak of the civil war Colonel Langdale commanded the cavalry in the Earl of Newcastle’s northern army. His service was not only employed on the battlefield, but also as an intermediary in secret negotiations with the Hotham’s to surrender Hull to the King. Marmaduke’s heart, however, was always in Yorkshire. In 1645, he wrote to Rupert for permission to return north: ‘let not our countrymen upbraid us with ungratefulness in deserting them … it will be some satisfaction to us that we die amongst them in revenge of their quarrels’. At Naseby, where Marmaduke led the royalist left wing of cavalry, the Northern Horse had been on the verge of mutiny. Only his strong personality kept them in the field, though they did not perform well. In October 1645, Marmaduke and his horsemen aimed to join the royalist Marquis of Montrose in Scotland but were defeated en-route. When in 1648 a Scottish army crossed the border in support of the imprisoned King Charles, Langdale joined them. He was, however, censured by the Covenanters for employing Papists in his force. After the civil war, poverty-stricken and in exile, Marmaduke retired to a monastery in Germany. At the Restoration he couldn’t attend the King’s coronation because of lack of funds. Fun Fact: Known as ‘the ghost’ due to his thin, pale appearance. 📅 D AY 2 📅 COLONEL JOHN OKEY 1606-1662 Born in London The Okey family held a number of properties around the capital and John went on to run his own ships chandlery business near the Tower. In 1630 he married Susanna Pearson, and at the outbreak of civil war – as a radical Baptist – enlisted in the Earl of Essex’s army as a cavalryman. He was soon promoted to the rank of major in Sir Arthur Haselrigg’s ‘lobsters’, so called because of their head-to-toe armour, and one of the war’s few cuirassiers regiments. By 1645, when Parliament formed the New Model Army, John was commissioned as a colonel of its only regiment of dragoons (mounted infantrymen with shorter-barrelled muskets). During the Battle of Naseby John’s dragoons lined the Sulby hedges, from where they fired on Prince Rupert’s cavalrymen. Afterwards, referring to his troops, he urged that Parliament: ‘should magnifie the name of our God that did remember a poore handfull of dispised men’. At the siege of Bristol in September 1645, John was captured during an attack upon the town but freed when it fell to Parliament’s troops. When the second civil war broke out in 1648, he helped Cromwell put down an uprising in South Wales and went on to sign the death warrant of King Charles I, after attending his trial. During Cromwell’s Protectorate, John disagreed with the abolition of the Rump Parliament and opposed Cromwell taking the mantle of Lord Protector. In 1654, he signed a petition calling for a free Parliament, for which he was briefly arrested. Upon the 1660 restoration of the monarchy he fled to Holland, where the ambassador, George Downing, had him arrested. Downing (whom ‘No. 10’ is named after) had once served in John’s dragoons as a chaplain, but casting off his surplice, and also turning his coat to the King, he betrayed his former commander. John was hung, drawn and quartered. In his last speech he reaffirmed his civil war role ‘was for the Glory of God, and the good of his People’ but stated he knew nothing ‘of the Tryal of the King … till I saw my Name inserted in a Paper’. Fun Fact : – One of the few regicides to be condemned to death by Cromwell and King Charles II. 📅DAY 3📅 PRINCE MAURICE of the RHINE 1621-1652 Born Kustrin Castle, Brandenburg His parents were the deposed King and Queen of Bohemia. At the age of 16, Maurice – named after the Prince of Orange – served in the Dutch army with his brother, Rupert, fighting against the Spanish. During the siege of Breda, the brothers crept up to the walls to eavesdrop and were able to pre-empt the garrison’s attack. Maurice next served in the Swedish army. In 1642, he accompanied Rupert to England to fight for their uncle, King Charles I. Clarendon wrote of him ‘The prince had never sacrificed to the Graces, nor conversed amongst men of quality, but had most used the company of ordinary and inferior men … and [he] understood very little more of the war than to fight very stoutly when there was occasion’. Fight stoutly he did, at Powick Bridge (where he was wounded) and then at Edgehill. 1643 was, however, not Maurice’s fondest year, despite notching up a number of victories. He was briefly taken prisoner during a skirmish at Chewton Mendip in June, then joined the King’s western army and led Cornish troops at the bitter siege of Bristol. Maurice was promoted to General of the Western army, though earned criticism from the outgoing commander and the people of the region over his men’s plundering. Whilst besieging Plymouth, Maurice fell ill. Dr William Harvey reported ‘His sickness is the ordinary raging disease of the army, a slow fever with great dejection of strength, and since Friday he hath talked idly and slept not’. But Maurice pulled through. At Naseby he fought with the royalist right wing of cavalry. When Rupert was dismissed after surrendering Bristol, Maurice supported his brother and they both left England in July 1645. Three years later they took command of a portion of the Royal Navy, which had defected, and following the King’s execution, continued to hold out against the English Commonwealth in these floating castles. They swarmed the Mediterranean, and then the West Indies, where they met with a hurricane off the Virgin Islands. For four days it battered and scattered the ships, and Rupert anchored to wait for news. But none came. Maurice and the Defiance were never seen or heard of again. 📅DAY 4📅 PHILIP SKIPPON 1598-1660 Born West Lexham, Norfolk The Skippons had risen from husbandmen to humble gentry and prized their educational links to Cambridge University. Philip, however, chose to join the army. Prior to this, no Skippon had ever distinguished himself militarily. From 1615 to 1638, he served in Protestant armies in Europe against those of the Catholic powers, where many civil war commanders cut their military teeth. Philip developed his Puritan faith here and in 1622 he married Maria Comes from the Palatinate. At the siege of Breda, leading 30 English soldiers, he beat off 200 Spaniards and cemented his reputation. One year after his return to England, the family moved to London and Philip secured the post of Captain-General of artillery. When the royal family fled the capital in 1642, he was appointment commander of the London Trained Bands, one of the most established in the country. He ignored King Charles’s summons to join him in York. Philip, the self-styled ‘Christian Centurion’ was always popular with his soldiers. They were like family; his military sons. At Turnham Green he gave a rousing speech ‘Come my boys, my brave boys, let us pray heartily and fight heartily. I will run the same hazards and fortunes with you. Remember the cause is for God, and for the defence of yourselves, your wives, your children’. At the disastrous 1644 Battle of Lostwithiel, where Parliament’s commander, Lord Essex fled, Philip was left in charge of the parliamentarian infantry. Surrounded, they were forced to surrender. Although granted generous terms by King Charles, the royalist soldiers robbed Philip of his scarlet coat, rapier and pistols, and he rode to the King to protest that this behaviour was ‘against his honour and justice’. The King summarily hanged a few perpetrators. At Naseby, in command of the infantry, Philip was dangerously wounded but refused to leave the field until victory was assured. In 1649, though commissioned as one of the King’s judges, he never attended the trial. Cromwell went on to style him ‘Lord Skippon’. Fun Fact - Philip wrote three books on moral and religious conduct for his soldiers. ‘If we have a good name. It procureth great contentment, And is more worth then great riches.’ He also warned against ‘hasty, hair-brained, humourists’. 📅DAY 5📅 JACOB ASTLEY 1579-1652 Born Melton Constable, Norfolk Jacob was born to be a soldier. This ‘honest, brave and plain man’, as Clarendon describes him, had an impressive military history, and if medals were issued back then, he’d have a chest full of them. At the age of 18, he joined Elizabeth I’s favourites, the Earl of Essex and Sir Walter Raleigh, in a naval expedition against Spain. On return, he fought the Spanish on land, under Maurice, Prince of Orange at Battle of Nieuport in 1600 (year of Charles I’s birth). In 1619 he married Agnes Imple, a Dutch heiress. In 1621, Astley joined Elizabeth of Bohemia’s household, who called him her monkey, or ‘Honest Little Jacob’ and became military tutor to her son, Prince Rupert. The schoolroom was temporary, however, and Astley was back in the midst of war, fighting bravely for Christian of Denmark (1626-27) and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (1629-32) during the Thirty Years War. At the siege of Bois le Duc, Jacob served in the trenches. In 1639, King Charles I, recognising his experience, appointed Jacob to lead the English infantry in a war with Scotland. Jacob was a distinguished soldier, but never made forays into the battlegrounds of politics. Clarendon says that in council, he ‘used few, but very pertinent words; and was not at all pleased with the long speeches usually made there’. Jacob was a royalist stalwart, serving as Sergeant-Major-General from 1642-45. At the Battle of Edgehill, he uttered the iconic prayer: ‘O Lord, thou knowest how busy I must be this day. If I forget thee, do not thou forget me.’ At Naseby, now Baron Astley of Reading, he fought like a lion, and despite inferior numbers, the royalist infantry very nearly succeeded. In 1645, after losing a son to the war, he took command of South Wales. He was later defeated at Stow-on-the-Wold, telling the parliamentarians ‘you have done your work, boys, you may go play, unless you fall out amongst yourselves’. Despite having retired to Maidstone, Kent, his reputation was so great that he was imprisoned in 1651 to prevent giving assistance to King Charles II, who had crossed into England with a Scottish army. Jacob died not long after his release in 1652. 📅DAY 6📅 HENRY IRETON 1611-1651 Born Attenborough, Nottingham Henry was reared from birth upon his parent’s puritanism. Religion became his daily bread and instilled his opposition to the Church of England’s ‘high church’ practices during Charles I’s reign. Henry’s family were minor gentry and he attended Trinity College, Oxford, and then Middle Temple, after which he most likely practised as a lawyer. He fasted often, beginning and ending meetings with prayers. Henry organised a 1642 petition against bishops and was commissioned as a cavalry captain in Parliament’s army before civil war broke out. He fought at Edgehill and Gainsborough, became Cromwell’s deputy-governor in Ely, and then in 1644, Quartermaster-General within Parliament’s Eastern Association. On the night before Naseby, Henry made a surprise attack upon the royalists. Next day, Cromwell successfully recommended him for the post of Commissary-General and he commanded the left wing of Parliament’s cavalry. After fighting courageously, he was wounded in the face and thigh and briefly taken prisoner. As an ‘Independent’ Henry desired freedom of religion (except for Catholics) and the separation of church and state. His biographer, David Farr, asserts him to be ’one of the most important influences on Cromwell … after God’ and in 1646, Henry married Cromwell’s daughter, Bridget. John Lilburne, a Leveller, described Henry as the ‘Alpha and Omega of the army’. Because he wrote every major document between 1647-49, Henry was titled ‘the penman general of the army’ by a contemporary journalist. In 1647, when the New Model Army army clashed with Parliament, Henry almost fought a duel with Denzil Holles. He was one of the Independents who arranged for the army to seize the King to avoid any settlement between monarch and Parliament, and instead drew up rival proposals. When the New Model Army began its Putney debates, he argued against ‘one man, one vote’ suffrage in favour of property rights, but turned down an award of land valued at £2000 per annum. In 1648, Henry drafted a remonstrance requesting ‘capital punishment’ for the King and persuaded the army to move against Parliament, resulting in soldiers occupying London and expelling moderate MP’s. Henry attended the King’s trial and signed his death warrant. He became Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1649 but died at Limerick from a fever. 📅DAY 7📅 PRINCE RUPERT 1619-1682 Born Prague, Bohemia When his parents fled into exile, the baby Rupert (one of thirteen) was almost abandoned, only discovered in a last-minute check of the palace. Rupert was raised in Holland where his family scrimped and saved on Dutch hand-outs. He was headstrong from a young age. At 11, his dog chased a fox into a hole. Rupert squeezed down and grabbed the hind legs but became stuck. Another man ended up the same way, and a third was needed to pull out this human/canine chain. His eldest brother tragically drowned, and then his father died while on campaign with Gustavus Adolphus’s Protestant army. Rupert’s recorded as being in floods of tears; a rarely associated emotion. At thirteen, the Prince of Orange took Rupert to the Siege of Rheinberg, but his mother recalled him. Mother and son battled regularly over Rupert’s soldiering, and her fears that if Catholics should capture him, he might be pressed to convert (a fear seemingly greater than the threat to his life!) Two years later he visited England and declared his wish to lay his bones in the country, before serving at the Siege of Breda. With his brother, Rupert fought the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor in a bid to take back the Palatinate but was captured. His mother’s fears soared. Rupert became a close prisoner for three years, but steadfastly refused to convert. He impressed his captors so, that they tried all ways to induce him to take a commission in their army. When he was released, partly due to pressure from King Charles I, Rupert pledged his life and loyalty to his uncle. At Naseby, rather than oversee the battle as Captain-General, he led the right wing of horse, which removed him from the field at a critical moment. He took the royalist cause to the seas, pirating against Commonwealth ships, and served in the French army. He was involved in all aspects of the Restoration: 🔹Science - metallurgy and gunpowder 🔹Arts - mezzotint engraving and actress-mistress, Peg Hughes 🔹Military - commanding the navy against the Dutch 🔹Exploration - Governor of the Hudson Bay Company 🔹Politics - friendship with anti-establishment Lord Shaftesbury Rupert’s bones were, indeed, laid in England; Westminster Abbey, 1682. 📅DAY 8📅 OLIVER CROMWELL 1599-1658 Born Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire Were it not for Oliver’s great-grandfather, I’d be writing about an Oliver Williams. But his great-grandsire married the sister of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor –because of the patronage and estates they gained from this benefactor, the family changed their name to Cromwell. Therefore, Oliver was of Welsh heritage – ironically, Wales was a staunch royalist stomping ground. He was one of eight surviving siblings; the rest were all girls and Oliver grew up as his mother’s spoilt favourite. He bunked off school but went to Cambridge and his early years seem to have been dissolutely spent in good fellowship and gaming along with rumours of petty theft. Oliver even described himself in youth as the ‘chiefest of sinners’, who ‘loved darkness’ and ‘hated godliness’. When Oliver was eighteen his father died, and he took responsibility for the family. He married Elizabeth Bourchier, daughter of a wealthy merchant family. Oliver’s parents were never well-off, but he had two extremely rich uncles, one of which fell into financial straits, lost royal patronage and offices, and as a result, Oliver’s own finances suffered. His doctor, Theodore Mayerne (also the royal doctor) noted Oliver’s extreme melancholy. He was elected to Parliament in 1628 and shortly afterwards prepared to emigrate, selling up and taking tenancy on a farm in St. Ives where he called workers for morning and midday prayers. In around 1630, the Puritan Oliver had a religious epiphany. Inheritance of an estate from his other uncle boosted his fortunes and he moved to Ely in 1636. Sir Philip Warwick recalls his first sight of Oliver in the 1640’s: ‘his voice sharp and untenable, and his eloquence full of fervour’. Though he didn’t fight at Edgehill, he noted the superiority of the royalist cavalry and instilled discipline and religious fervour in his own men. His spectacular victories led to his appointment as second-in-command of the New Model Army. At Naseby, Oliver led Parliament’s right wing and defeated their opponents, but, crucially, fought on instead of chasing after them. Four of nine children pre-deceased Oliver and the loss of his daughter Elizabeth particularly affected him weeks before his own death. Regicide. Irish atrocities. Lord Protector. The House of Cromwell ruled for 6 years. 📅DAY 9📅 SIR THOMAS FAIRFAX 1612-1671 Born in Denton Hall, near Otley in Yorkshire Tall, and with a dark complexion, he was nicknamed ‘Black Tom’ and raised by his grandfather, Baron Fairfax of Cameron. Thomas studied at St. John’s College, Cambridge and published a volume of poems called The Employment of my Solitude. Despite being a ‘lover of learning’, he was present at the siege of Bois-le-Duc aged 17 and then fought in the Low Countries. It is here that he met his wife, Anne, daughter of the English commander, Lord Vere. In the Bishops Wars with Scotland (1639/40) he fought in the King’s English army and was knighted in 1641. It was the opinion of Bulstrode Whitelocke that Thomas was ‘of as meek and humble a carriage as ever I saw in great employments’. But, like Jekyll and Hyde, Bulstrode said that in battle, he was ‘more like a man distracted and furious than of his ordinary mildness’. Thomas was also stubborn, as proved in 1642, when he had joined a group of protestors to petition King Charles against raising a royal bodyguard. They were held back, but Fairfax managed to evade the soldiers, riding up to the King and pushing the petition against his saddle. Despite mixed success in the early years of the civil war, it was clear that Thomas had a military talent, as Brigadier Peter Young, founder of The Sealed Knot re-enactment society, acknowledged. ‘The Yorkshire Parliamentarians had survived amidst a sea of enemies thanks to the talent and fighting spirit of Sir Thomas Fairfax’. But Young also adds that Thomas was ‘an inarticulate man and politically ineffective’. During the war, Thomas was wounded in the wrist and then the shoulder, and in the 1644 Battle of Marston Moor, he escaped capture by removing the parliamentarian field sign from his hat. In 1645, he reluctantly accepted the post of Commander-in-Chief of the New Model Army and after forming them into an effective force, led them at Naseby. Thomas took no part in the trial of the King, though his wife heckled the court & questioned its legality. Fun fact: After a night reconnaissance on the eve of Naseby, he forgot his army’s password and was held by a sentry in the rain. 📅DAY 10📅 KING CHARLES I 1600-1649 Born Dunfermline Palace, Scotland After birth, the sickly Charles was hastily baptised on the assumption he’d not see the night out. When his father became King of England in 1603, the family left Charles in Scotland; aged two and a half, he couldn’t walk, nor talk. Despite weak joints of the knees, hips and ankles, he did possess a strength of mind and refused to be examined. His caring nurse prevented such treatments as cutting the string beneath his tongue, and Charles’s determination pulled him through, even mastering horse riding. One of his serving women was involved in the Gunpowder Plot, which must have been a defining moment in his life. Charles idolised his tall, strong, charismatic brother, Henry, sending him gifts and writing that he would ‘give anie thing that I have to yow’. Charles flourished; he danced, played tennis, sang and devoured books. He was close to his mother, who called him her ‘little servant’ and with whom he planned court masques; plays in which they acted. When his brother died in 1612, Charles was distraught and his father withdrew, leaving the twelve-year-old to arrange Henry’s funeral. He escorted his sister to her wedding, learned to speak French, Spanish and Italian, and began collecting coins, medals and paintings. King James made his favourite, George Villiers, a duke. From humble roots, the man became so close to the royals that he was treated as one of the family. Charles resented him, yet admired him. When Charles’s sister’s family lost their lands in the Palatine, he sought marriage in order to bring military aid to Elizabeth and married the French Princess Henrietta-Maria. Although of sober character compared to his vulgar father, Charles had less tact and did not manage Parliament well. On his accession to the throne they refused to grant him revenues for life, like his predecessors, leaving him bitter. He ruled without them for eleven years while Europe was torn apart by war. Charles, finding solace in structure and order, attempted to impose a unified prayer book, resulting in two wars with Scotland, which necessitated Parliament’s support, and there was an uprising in Ireland. King and Parliament’s mutual vulnerability and mistrust led to wars that consumed all three kingdoms. I hope you've enjoyed the ten biographies to mark the special anniversary of Naseby. Take a look at the other articles on my blog for more civil war information. Thanks!

By M Turnbull

•

27 May, 2020

Nestled into the North West of England was the magnificent fortress of Lathom House, seat of the Earl and Countess of Derby. By March 1644, the parliamentarians had surrounded this major thorn, that stuck in the side of Puritan Manchester. The parliamentarians didn’t expect a prolonged siege, especially considering that Lord Derby was away tackling a rebellion on the Isle of Man. But the island rebels had probably done a great favour to Lord Derby, because it meant that his redoubtable wife was left in charge of Lathom House when the parliamentarians closed in. Both Lathom and Lady Derby had impeccable backgrounds. King Henry VII had supposedly modelled Richmond Palace on Lathom, and Lady Derby was a fitting chatelaine, being a granddaughter of the Dutch Prince of Orange, William the Silent. She was also a niece of the Dowager Electress Palatine – Louisa Juliana – who happened to be none other than the grandmother of Prince Rupert of the Rhine. Rupert himself was readying an army to secure the North-West and relieve Lathom. To literally buy time Lady Derby had agreed to give over the revenues of the family estates to the parliamentarians, lulling them into a false sense of security, but allowing her to build up her garrison and supplies. From the pulpit, Puritan preachers compared her to the Scarlet Whore of Babylon, whipping up the region and its soldiers into a furore against her. Lady Derby’s parliamentarian opponent was Sir Thomas Fairfax, a Yorkshireman with 2000 men who invited her to surrender with an explanation that: 📜 'Your Ladyship keeps Lathom with a garrison of soldiers in it, which doth many injuries to the army and much hinders them, and is a receptacle and great encouragement to the Papists, and disaffected persons in those parts; I should not do my duty if I neglect the means to remove that mischief…’ The Calvinist Lady Derby replied that she wished for one week's consideration and wondered why she was being asked to give up her lord’s house ‘without any offence on her part done to the Parliament’. Fairfax declined the delaying tactic and offered to speak with her if she should come out to meet him in her coach. Lady Derby’s second response highlighted her common traits; stubborn, courageous, haughty and resolute; she was clearly not going to surrender, nor entertain the very least thought of it. Replying that ‘notwithstanding her recent condition, she remembered both her lord’s honour and her own birth, conceiving it more knightly that Sir Thomas Fairfax should wait upon her, than she upon him’. She went on to make her intentions crystal clear: 📜 'Although a woman, and a stranger divorced from my friends and robbed of my estate, I am ready to receive your utmost violence, trusting in God for protection and deliverance.’ From behind her twenty-five foot wide moat, double ring of walls, and beneath the shadows of nine towers, each bristling with six cannons and topped with gamekeepers-cum-snipers, the countess watched and waited. At her disposal were 300 soldiers commanded by a Scottish major, and six captains who all answered to her. From the Eagle Tower that crowned the centre of the fortress the family standard defiantly fluttered their motto ‘Sans Changer’ or ‘nothing changes’ – symbolic of her stoicism. Lathom stood in a marshy hollow, with woods bordering it, which meant that if any parliamentarian gun was to fire upon her, it would be forced to do so from open ground within range of her own. When Fairfax, her noble guest, entered Lathom's inner sanctum, he must have been impressed by the show that Lady Derby put on for him - her soldiers lined each side of the courtyard right from the gate to the great hall. It must not have taken much talking to see that the Countess’s views were ‘sans changer’ and that she stood as resolute as ever. But talks between one of Fairfax’s officers, who had accompanied him, and the Countess’s chaplain did throw up an interesting fact. The chaplain let slip that the garrison had only 2 weeks of provisions, therefore Fairfax merely had to play a waiting game. With this in mind and considering it ‘ignoble and unmanly to assault a lady of her high birth and quality in her own house’, Fairfax left the siege to his subordinate, Alexander Rigby, MP for Wigan, with instructions not to storm the house, but to starve them out. After two weeks had come and gone, the countess and her band showed no signs of struggle – indeed, they were emboldened enough to charge out of their gates and kill thirty of the besiegers who were slowly building earthworks with which to mount their offensive The Earl of Derby wrote to Fairfax to requested permission for his wife and family to leave the house and join him, though he stipulated that this was only if his wife consented. She did most certainly did not, and the siege continued apace. Captain Farmer led half the garrison (140 men) out of the house and spiked the parliamentarian guns, killing a further 50 soldiers. This entire action was supervised by Captain Fox, who, perched up in the Eagle Tower, used flags as signals. Rigby was desperate. He took delivery of a state-of-the-art mortar from London, news of which would have unnerved most garrisons, but not Lady Derby’s. She kept to a strict routine and lived and worshipped cheek by jowl with her men. They were in it together, keeping calm and carrying on, inspired by the countess and her two daughters who joined them four times every day for prayers. Therefore, when the dreaded mortar cast 80lb boulders and grenadoes at them, the countess continued unabashed. One bomb fell near to where she was dining with her daughters and officers – no doubt she continued the meal – while another destroyed her bedroom window. She had firefighters standing ready with wet hides, for it was known that the mortar could hurl fireballs, and in April Rigby sent a messenger to give due warning that these would be unleashed. Lady Derby received the man in the courtyard, surrounded by her entire garrison so that every soldier might hear her reply. ‘Thou art only a foolish instrument of a traitor’s pride,’ she told the man and then famously declared: 'Go back to your commander and tell that insolent rebel, he shall have neither sons, goods, nor house. When our strength is spent, we shall find a fire more merciful than Rigby’s, and then, if the Providence of God prevent it not, my goods and house shall burn in his sight; myself, my children, and my soldiers, rather than fall into his hands, will seal our religion and our loyalty in the same flames.’ Her troops cheered as she tore up Rigby’s summons and themselves declared that they would die in the king’s cause and for the countess’s honour. To chants of ‘God save the King!’ the messenger left to relay all that he had witnessed. At dawn the following day, Lady Derby left the gates of Lathom House. She walked into ‘No Man’s Land’ and encouraged her troops who went on to beat the parliamentarians back from their positions. The royalists proceeded to level the enemy earthworks and lift the scourge that was the mortar onto a trolley, whereupon they dragged the beast all the way back to the house. With his prized gun now taken prisoner, and Prince Rupert close by with a royalist relief force, Rigby must have despaired. The Earl of Derby joined Rupert’s army and distributed £3000 between them to help speed up their march to his wife. After 12 weeks of siege, Rigby withdrew his army from Lathom, but he could not escape the prince, who defeated him at Bolton. Having despatched the countess’s foe, Rupert finally arrived at Lathom where he received her thanks. Celebratory gifts were exchanged; Rupert received a ring worth £20, while one of his officers was presented with four expensive candlesticks, such was her gratitude that the countess gave what valuables she had at hand. For his part, Rupert presented the countess with twenty-two flags which he had taken from Rigby’s force, which Lady Derby hung up in the heart of her great hall. If you've enjoyed reading about the British Civil War, you can find more articles on this blog, or more details about by civil war novel, Allegiance of Blood on this website. Click the links below for more details. Paperback - £7.99 E-book - £1.99

By M Turnbull

•

03 May, 2020